Jackie Gleason Biography

Christened “The Great One” by Orson Welles after a long and liquid night on the town, Jackie Gleason embraced all that the title implied. Christened “The Great One” by Orson Welles after a long and liquid night on the town, Jackie Gleason embraced all that the title implied.

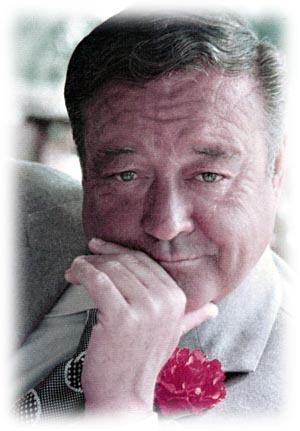

His penchant for fine food, generously poured scotch and beautiful women; his ability to dominate a room, a stage or the screen; his taste for custom-made suits, monogrammed shirts and the ubiquitous red carnation; his appetite for the biggest, the best and just a dollar more than the other guy made, all became a part of the Gleason legend which began on Brooklyn’s Herkimer Street in 1916.

Born Herbert Walton Gleason, Jr. and baptized John Herbert Gleason, His mother, Mae, called him Jackie and raised him alone as a working mother after his father, Herbert, left the family in 1925. His older brother Clement, always frail and sickly, died when Jackie was only three.

Although Mae was successfully determined that young Jackie live the Catholic faith and receive the sacraments, she could do little to encourage his academic life.

A fairly disruptive student, he limited his deep thinking to stickball, pool halls and pranks. Limburger cheese lavishly spread on the radiators of P.S. 73 ensured a free day while janitors searched and destroyed. And no one ever found out for sure who released the snake in the orchestra pit of the Halsey Theatre. When he won the role of MC in the eighth-grade presentation, the assembly cheered his original performance. The teachers cheered his departure.

Jackie had known since he was six, when his father brought him to a matinee of silent films and Vaudeville at the Halsey, that he wanted to face an audience for the rest of his life. “A great feeling of friendship came from the audience,” he said. School was simply an obstacle to overcome. He began appearing at service and fraternal organizations where he met and worked with his future wife Genevieve Halford. After less than a year, he abandoned high school.

In 1934, during the Great Depression when unemployment wavered between 21% and 23%, Jackie Gleason had steady work. Not lucrative, but steady. His resume listed The Majestic, The Central, The Folly and The Halsey Theatres in Brooklyn, while he played Club Miami and the famous Empire Burlesque in Newark. He often worked two or three theatres at a time, skipping from Brooklyn to Jersey and back again in a single night.

Because he was a quick study he became house comic at The Empire, a promotion which terrified him at first. On Sunday morning he’d receive a script and then perform that same Sunday night. He quickly learned from the circuit pros that there were no scripts set in stone, no time for rehearsals, and that “if you wanna make it, kid, you have to make it your own.”

Two months after his nineteenth birthday Mae Kelly Gleason passed away. After the traditional wake in their railroad apartment, Jackie turned out his pockets, found subway fare and moved in with two fellow thespians in Manhattan. Money was so thin that a meal often consisted of cafeteria soup: a mixture of hot water and all the free condiments that Horn and Hardhart’s offered. Jackie continued working Jersey and Brooklyn, and expanded to Philadelphia and some of the bigger clubs on Long Island. He married Genevieve in 1936 and they honeymooned at The Empire Theatre.

By now Jackie was receiving positive press and began working clubs in Manhattan which landed him a role in Along Fifth Avenue. The show opened on Broadway to fair reviews. Each night after the final curtain he worked The Torch, Leon and Eddies or Club 18 on 52nd street where all the action was. “I’d be lost if I didn’t work on the floor until two or three in the morning,” he said. Jack Warner had seen him at several spots and finally offered a contract he couldn’t refuse.

By 1941, Jackie had two daughters, Geraldine and Linda, living with his wife on Long Island while he lived alone in Hollywood. By day he sat around the set at Warner Brothers and ultimately made eight fairly forgettable films. By night he played supper clubs. He traveled back to Broadway where his reviews were brilliant for Follow The Girls, and Billy Rose hired him for his glitzy, star-studded night club, The Diamond Horseshoe. He reconciled and separated again from Gen, and played clubs from New York to L.A. until he won the television title role in The Life of Riley (1949).

The sitcom lasted a year and from that exposure he was offered a short stint on Dumont’s Cavalcade of Stars. Two years later, still in command on Dumont, CBS invited Ralph Kramden, Joe the Bartender, Reggie Van Gleason III and The Poor Soul, to take up residence on its network.

Gleason signed with CBS on November 23, 1951. The Jackie Gleason Show, which commanded more than 160 team members as production staff, actors, dancers, musicians, choreographer (June Taylor), technical crew, wardrobe and make-up, was broadcast live for the first time on September 20th of the following year. The ratings soon soared to 42%. Jackie became “Mr. Saturday Night.”

In 1955, Gleason’s format changed to accommodate the wild popularity of The Honeymooners. The idea was to split Gleason’s time slot into two half hour shows: The Honeymooners, and Stage Show, a music and variety combination hosted by the Dorsey Brothers. Both shows were owned by Gleason. The 1955-56 episodes of The Honeymooners became known as the "original thirty-nine."

During the 50’s and 60’s, Gleason recorded 43 albums of mood music, wrote the theme songs for his show (“Melancholy Serenade”) and The Honeymooners (“You’re My Greatest Love”), built a round house in Peekskill, New York, starred in nine films, garnered an “Oscar” nomination for The Hustler, won a “Tony” for his Broadway performance as Uncle Sid in Take Me Along, hosted or performed in 30 television specials, and moved his new television show (American Scene Magazine) and its entire entourage via train to Miami, Florida. In 1969, he and Genevieve divorced.

In the next decade and a half, Gleason married (1970) and divorced (1974) Beverly McKittrick and then married (1975) June Taylor’s sister, Marilyn. He starred in eight films including Smokey and the Bandit I, II, and III. In addition, he hosted or guest-starred in 17 television specials, created the annual Inverrary Golf Classic, filmed five Honeymooners specials, released The Lost Honeymooners for syndication, (which includes all episodes other than those filmed during the 1955-56 season). In 1978 he underwent quadruple coronary bypass surgery.

In 1986, Jackie was diagnosed with diabetes and phlebitis, but he knew his condition was more serious. “I won’t be around much longer,” he told his daughter at dinner one evening after a day of filming Nothing In Common.

On June 24, 1987 Jackie passed away from colon cancer at his home in Inverrary. His Memorial Mass was celebrated by the auxiliary Bishop of Miami, His Excellency Bishop Norbert Dorsey who said, “Throughout his professional life (Jackie) kept the heart of a child. A whimsicalness that cheered up a sad and tired world.” He is buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery in a lavish above-ground mausoleum that suits “The Great One.” Etched into the marble stairway leading to his sarcophagus reads the inscription, “And Away We Go.”

|